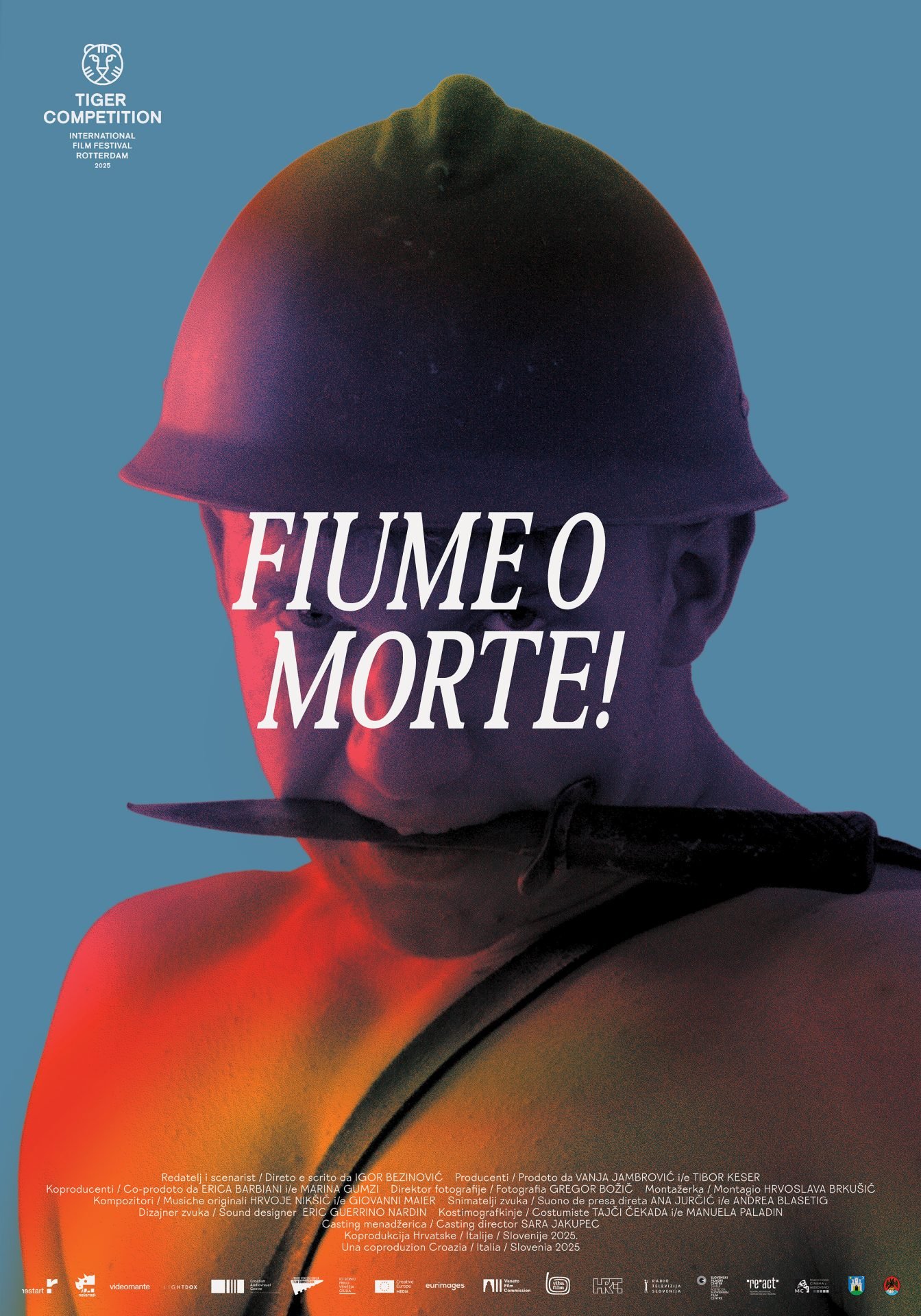

The film’s poster. Trailer here.

[WM: Fiume o morte! [Rijeka or Death!] by Igor Bezinović, fresh winner of the Rotterdam Film Festival, is an extra-ordinary work in every respect. The film reconstructs the so-called «Impresa di Fiume» [Rijeka Enterprise] of 1919-1920, at long last from a non-Italocentric perspective, surprisingly enacting the talking back of anticolonial and decolonial literature: the reversal of the point of view, the counter-narrative. Here such a narrative is entrusted to the memories –family, archival, urban, architectural memories– of the city itself, the Fiume/Rijeka that was then invaded.

Gabriele D’Annunzio and his legionnaires acted in advance of Italian imperialism in the Balkans, they were its spearheads. The blitz was intended to make up for the so-called “mutilated victory” in the First World War. “Mutilated,” because at the Paris negotiations the Kingdom of Italy had failed to get all the former Austro-Hungarian lands it was aiming for. Missing from the list were Fiume and Quarnaro (or Carnaro, as it used to be called), as well as the much-coveted Dalmatia.

Since the 1990s it has been in vogue to reevaluatethe occupation of Fiume “from the left” or in a “libertarian” sense. In the timely review we publish today, the Nicoletta Bourbaki collective remarks on the unfoundedness and narrow italocentrism of such interpretations. Ignorance of non-Italian sources is one with indifference to the Croatian-, Hungarian-, German-, and even Italian-speaking inhabitants of Fiume/Rijeka who were opposed to annexation. They really do not come to mind, they are subjectivities excluded a priori, tacitly declared non-existent. What they experienced and suffered does not matter.

What remains out of the picture is the imperialist and especially racist aspect of that invasion. To give just one example, here is how D’Annunzio expressed himself in his Letter to the Dalmatians, 1919:

“The filthy Croat climbed up the ashlars of the Venetian wall, like a monkey on the rampage, and with an iron scrape scarped the Winged Lion […]. That mishmash of Southern Slaves that under the mask of recent freedom and under a bastard name poorly conceals the hateful old stump…”

Against the hated “s’ciavi,” [a derogatory term for Slavic people] D’Annunzio’s legionnaires carried out squad-like assaults and actual raids, such as the one against the village of Baška on the island of Krk.

When, amid great sighs of relief from the Fiumans, the legionnaires had to flee, Fiume/Rijeka became an autonomous city-state, but it was short-lived. D’Annunzio’s breakaway had anticipated further expansions eastward by Italian imperialism: in March 1922 a fascist-inspired coup overthrew Riccardo Zanella‘s autonomist government, and in January 1924 Fiume/Rijeka was annexed by Italy. As for Dalmatia, it was taken in 1941 with the Nazi-Fascist invasion of Yugoslavia. Which D’Annunzio, who died in 1938, could not see. He did, however, make time to celebrate as a coherent continuation of his “enterprise” – and he was right – the Fascist invasion of Ethiopia.

Fiume o morte! talks back, it throws the narrative back at us. It does it from the eastern shore of the Adriatic and from unexpected angles, squaring stereotypes. Most importantly, it does it collectively. The effect is invigorating.

On the occasion of the film’s – now imminent – arrival in several Italian cities, the Federazione delle Resistenze is organizing initiatives and debates. We recommend keeping an eye on the website and/or the Telegram channel.

Happy reading, happy viewing, happy meetings.]

By Nicoletta Bourbaki *

Croatian Rijeka director Igor Bezinović says his upcoming film entitled Fiume o morte! documents the first time a Roman salute was captured and imprinted on film. It was September 1919, the scene took place in the city of Fiume/Rijeka, and stretching out in front of the camera his right arm in the salute that just three years later would become the hallmark of Italian fascism, and later also of German Nazism, was the Italian poet and playwright Gabriele D’Annunzio.

D’Annunzio is the protagonist of Bezinović’s extraordinary film, a Croatia/Italy/Slovenia production soon to be released in theaters, a true unidentifiable narrative hybrid recounting the sixteen months of the Italian occupation of the city of Fiume/Rijeka. An invasion led by D’Annunzio himself, formally opposed by the liberal governments of the Kingdom of Italy, but in fact supported by its army, and amply funded by Italian banks, capitalists and Freemasonry. As Bezinović notes in the same interview, in a chilling historical parallel Fiume or Death! comes out in the weeks when the Roman/Dannunzian/Nazifascist salute is back in the news via Elon Musk.

Frame from a film dated September 1919 included in Fiume o morte!

Notwithstanding the tragic events it evokes, Bezinović’s work is anything but chilling. Rather, its narrative style is marked by a joyful and well-planned strategy that rests on the one hand on the hybridization of textual, iconographic and filmic types, and on the other hand on the idea of making a participatory work, a kind of community project that involved the citizens of Fiume/Rijeka in the retelling of a removed and misunderstood page in the history of their city and of all of Europe.

In the opening sequences we see some still shots showing today’s bridges over the Rječina/Fiumara River, to which are then superimposed photos and drawings of the same bridges dating back to Christmas 1920, i.e., after the day D’Annunzio, as told by the voice-over, ordered their senseless and unnecessary destruction. At the time, just before flowing into the Adriatic, the river divided the towns of Rijeka/Rijeka and Sušak, now parts of the same city.

Sušak, on the eastern bank, was inhabited mostly by people who spoke Croatian. On the other shore, the western shore, the Istrovenetian Fiuman dialect was predominantly spoken. This multilingual aspect, which historically connotes the entire Northern Adriatic region, is the basis for the first of many perturbing elements of the film: in the first ten minutes the comments and dialogues are in Croatian with Italian subtitles, but from the moment the citizens/interpreters start to reenact the historical events, many of them switch to Fiuman dialect, which becomes the language of the film until the moment of the defeat of the “legionaries.”

The effect on the Italian viewer is both comical and estranging: Fijumanski today has almost disappeared from everyday use. The director himself and the citizens of that city tell us how time and events have made that dialect a minority, the sound of which, however, in many and many evokes memories of family life related to the figures of parents, grandparents and great-grandmothers.

Director Igor Bezinović.

It is an effect that Bezinović pursues intentionally, to make the Croatian public “aware that Italians did not arrive here with fascism, but are the indigenous population of Rijeka.” In a city that “in the twentieth century found itself in eight or nine different states,” these reenactments demolish rather than enhance a supposed italianità or any exclusive national identity of the city. Instead, they signal the unpredictable and ungovernable human vitality of places, which in the layering of historical events and state sovereignties end up creating new identities again and again.

Bezinović uses the architecture of the city in the same way. In Fiume/Rijeka structures and buildings from the Habsburg era were later joined or overlaid by those dating from the Italian fascist dictatorship, then those from the long socialist period, and finally the current ones following Croatian independence. In their period costumes, the characters act against this composite backdrop of co-present historical layers, increasing the strangeness of the vision.

The re-enactment of the invasion is introduced by an actual making of the film itself. The crew walks around a marketplace asking passers-by if they ever heard of D’Annunzio. Most answer that they don’t have a clue, until someone starts answering, “yes, he was a fascist.” “A fascist who occupied Rijeka and its environs, there are also fascists today unfortunately.” Even a group of Italian tourists say they know who D’Annunzio was but that “I don’t like him, because he was a fascist.”

The crew also stops all the bald men and asks them to come in for the audition, implying that they will choose one to play the poet. Instead, they choose them all, and D’Annunzio will be played in turn by seven different amateur actors, including journalists, members of Croatian punk-rock bands, and even a retired Carabinieri officer from Turin who now lives in the Quarner city.

Then the actors walk around the city in uniform, reenacting topical scenes from the occupation. D’Annunzio gives fiery speeches in front of nobody, or in front of a few people who shake their heads or laugh.

Frame from Fiume o morte!

The happy intuition at the basis of Fiume o morte! as a collective work generates moments of exquisite improvisation, often hilarious but also very meaningful, such as when a lady stops in front of an actor dressed as a legionnaire and says to him:

– What are you dressed up as?

– A soldier in D’Annunzio’s army.

– D’Annunzio? That’s all we needed! You’re a handsome guy, why are you wasting your time like this? You should go to the disco, flirt with girls….

– I’ll do that later, madam, right now I’m just playing a role….

– D’Annunzio! Just him, that’s all we need…

And she leaves muttering contumelious words.

The turn that events would take after the start of the Invasion in September 1919 can already be guessed from the first weeks of the Italian “presence,” when a growing number of young and very young Italian militiamen soon pose themselves in derisive, arrogant, and finally violent hostility toward the population, particularly the Croatian, Hungarian, and Slovenian inhabitants, but also toward part of the Italian citizens, who at the time accounted for slightly less than half of the total. Out of a population that in 1920 numbered about fifty thousand, young people from every corner of Italy -“a youth that had nothing definite to do at home”- would end up being ten thousand, completely unaware of where they were, convinced by nationalist rhetoric that they were the vanguard of a superior civilization, and completely unprepared even militarily.

The inevitable chauvinist turn of the invasion begins with the partial decapitation of the city’s symbol, the double-headed eagle wrongly considered an Austrian emblem, actually representing precisely the autonomy that Rijeka, like Trieste, had carved out for itself vis-à-vis the Austrian crown thanks to its role as a port of the Empire and its cultural and ethnic multiplicity.

The violence reaches its peak after three months, with the devastation of polling stations for the plebiscite that D’Annunzio called for and then cancelled when a glimmer of lucidity in the mind of the poet, often “stuffed up with cocaine”, makes him guess that the citizens will vote compactly against his occupation.

Blatant confirmation followed when D’Annunzio introduced sanctions and fines for the press that criticized his junta, a ban on public meetings, compulsory conscription for all Fiumans between 18 and 22 years old, a ban on strikes and worker propaganda of communist, socialist and anarchist inspiration, and even a ban on carnival celebrations.

Finally, in July 1920, comes the gangster violence against “non-Italian” public and commercial establishments, concerted with the similar and more notorious burning of the Narodni Dom [People’s House] in Trieste and the similar actions in Pula, taking as a pretext the so-called “Split incidents” between some Italian nationalist militiamen and the Croatian citizens of that city.

Fiume o morte! sagaciously rebukes a strategy used by European far-right exponents to deflect themselves from the inescapable accusation of being heirs of Nazi-fascism and to reclaim their virginity. A strategy that consists basically in labeling their own disreputable progenitors as “left-wing,” pivoting on arguments devoid of any historical basis and yet relaunched without any friction by mainstream journalism: Mussolini had been a socialist, ergo fascism is left-wing stuff, not right-wing. The Nazis were national-socialists, hence socialists, so they too left-wing stuff.

Giorgia Meloni‘s statements on the occasion of Holocaust Remembrance Day also respond to the same logic. She said that Italian fascism was only an “accomplice” of the Shoah. Historian Anna Foa pointed out the vagueness of the term, given the ascertained fact that the [collaborationist] Republic of Salò took charge of deportations to extermination camps on behalf of the Germans and with equal zeal. Such vagueness allows Meloni to hint at an abjuration of fascism, for those who want to hear such a thing against all evidence. Moreover, at this precise moment in history, vagueness serves to backfire the accusation of anti-Semitism against those on the left who protest the Israeli massacres in Gaza and the West Bank.

On closer examination, the same strategy underlies the narratives that over the decades have attributed to the so-called “Impresa di Fiume” a particular revolutionary and libertarian spirit, over-interpreting the presence in that context of eccentric characters, artists and avantgardists, individuals with an unbridled sexuality and a passion for drugs, and on the basis of crass misinterpretations of passages extrapolated from D’Annunzio’s toxic proclamations – in particular from the never-implemented “Charter of Carnaro” drafted by the syndicalist Alceste de Ambris.

A textbook example of these narratives, and the cause of their persistence since the mid-1990s in some circles of the “antagonist” left, was the self-styled “anarchist” reading of that experience given by Hakim Bey in his TAZ: Temporary Autonomous Zones, where D’Annunzio’s occupation is counted among “Pirate Utopias”, ignoring, or pretending to ignore, that such an interpretation completely removes its nationalist, reactionary and racist nature, as well as being completely unfounded on the historical level.

Bezinović himself in interviews about the film recounts how as a student, reading TAZ and then Claudia Salaris‘ essay, Alla festa della rivoluzione (2002), he was seized with enthusiasm, but also with the suspicion that something was not quite right. He realized later that only rigorous historical research, starting from the unequivocal fact that the “enterprise” had been first and foremost a military occupation, could enable him to separate the historical facts from the myth that had been built around them.

In Italy, on the contrary, the most emblazoned signatures of “historical popularization” gave that myth the dignity of historiographical truth – resting on the assumption “but D’Annunzio was not a Fascist” – and going so far as to describe the armed invasion of Fiume/Rijeka as a forerunner of social uprisings of a completely different nature that would take place in Italy half a century later.

It is to be expected that precisely these kinds of arguments will be used by some reviewers, more or less openly aligned to the right, to attempt to diminish the value of Fiume o morte! Perhaps by denouncing the outrage of a work on the “Vate” made by a Croatian director. A complaint, however, which should at that point call into account the meritorious support for the film’s production from Italian institutional bodies such as the Ministry of Culture, the Friuli Venezia Giulia Audiovisual Fund, the Friuli Venezia Giulia Film Commission, the FVG Region, and the Veneto Film Commission. The Vittoriale Foundation itself [the body administering D’Annunzio’s cultural heritage] also collaborated by allowing archival research and filming in the monumental complex.

Fiume o morte! has, among its many merits, that of putting D’Annunzio’s role in the right perspective in the historical phase in which fascism was taking hold and Mussolini was about to come to power. The point, of course, is not whether D’Annunzio called himself a fascist, or even to what extent Mussolini managed to “maneuver” him. The point is what, more than anyone else, D’Annunzio managed to establish thanks to the mythical “Impresa”. The film recalls the many contacts between the warmongering poet and Mussolini, including the latter’s visit to Fiume to deliver a large sum of money.

Trieste/Trst, 13 July 1920. Fascists set fire to the Narodni Dom, the headquarters of the city’s Slovenian associations.

Also significant is D’Annunzio’s own enthusiastic support for the burning of the Narodni Dom in Trieste in July 1920 – the seat of the city’s Slovenian and Croatian cultural and economic associations, the devastation of which was the founding act of fascist squadrism. The mastermind and promoter of that crime was Francesco Giunta, a staunch supporter of the Invasion of Rijeka and the one who would later, in 1922, take charge of reoccupying the city when D’Annunzio had already been gone for more than a year.

In some particularly emblematic frames, we see a photo of D’Annunzio among a group of legionnaires. Behind them is a wall inscribed with swastikas and Celtic crosses, as if to remind us that the judgment on that “enterprise” should also be measured by keeping in mind what it brought about in the years that followed, all the events that were inspired precisely by the warmongering, nationalist and colonialist rhetoric devised by D’Annunzio himself.

The official synopses describes Bezinović’s directorial approach as “provocatively punk,” but such a description runs the risk of diminishing the film’s narrative quality and, above all, its great intelligence. Fiume o morte! could fit right in among the narratives that, in the Italian literary context, Wu Ming 1 has called Unidentified Narrative Objects. A definition that does not have to do with the mere mixing of genres –which in the film move from documentary to comic, from historical-biographical to grotesque, from dramatic to musical– rather than with the use of different textual typologies.

Among the many elements that make for an uncanny viewing, a prominent place belongs to the way Bezinović’s own screenplay manages to use diverse materials in an amalgam that is bizarre but far removed from any aesthetic frivolity. Every element, including the improvisational moments captured by the camera, is strictly necessary to the reconstruction of a complex episode that overturns the typically Italian description of D’Annunzio as poet, patriot and even revolutionary.

The highly effective use of archival photographic and filmed materials honestly acknowledges D’Annunzio’s gifts as a propagandist –in this sense, according to Bezinović, “one of the greatest talents in human history”– but the reversal makes him emerge as the vain and grotesque buffoon that he always was, and his “enterprise” starts in the key of clowning and ends in tragedy.

_

* Nicoletta Bourbaki is an Italian collective doing research on online historiographical revisionism, historical-themed fake news, and the rehabilitation of fascisms in all its variations and manifestations. The group was formed in 2012 following a discussion on this very website and has many investigations and several publications to its credit.

In 2017 that conceived and edited the special La storia intorno alle foibe [The History Surrounding the Foibe] for the magazine Internazionale.

In 2018 they published online the educational guide Chi dice questo? E perché? [Who Says This? And Why?]

In 2022 they published the book La morte, la fanciulla e l’orco rosso. Il caso Ghersi: come si inventa una leggenda antipartigiana [Death, the Maiden and the Red Ogre. The Ghersi case: how an anti-partisan legend was invented].

In 2024, they completed the most comprehensive research ever conducted on the figure of Norma Cossetto, the circumstances of her death, and the neo-fascist fake news that envelope it.

The collective pseudonym “Nicoletta Bourbaki” is a transfeminist détournement of “Nicolas Bourbaki,” a very male group of French mathematicians active from the 1930s to the 1980s.

Nicoletta Bourbaki is on Medium and on Telegram.

–

–